Suffocating the Ocean : Climate and Ocean Health

- Climate, Featured, News, Oceans

- Featured, ocean health, ocean oxygen, ocean warming

- April 29, 2016

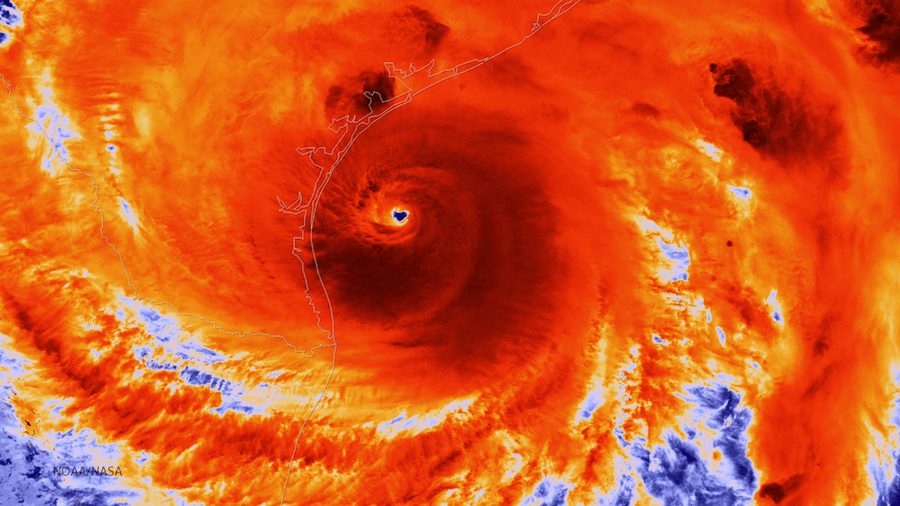

Ocean breathing

From the shallows down to its yawning depths, the ocean gets its oxygen from the surface, supplied either by the atmosphere or from the release of oxygen in phytoplankton through photosynthesis.

Scientists have long known that one expected consequence from a warming climate is a gradual drop in the amount of oxygen dissolved into ocean waters as they absorb extra heat trapped in the atmosphere by increasing concentrations of greenhouse gas.

Warming surface waters absorb less heat. The oxygen that does take into the surface waters has a harder time circulating down into the deeper water due to the expansion of the warmer upper layers. This expansion makes the surface water lighter than the water below it, less likely to sink and circulate.

As with all climate phenomena, ocean oxygen concentration at the surface is in constant flux from the natural variability of warming and cooling. A particularly cold winter in the North Pacific, for example, will soak up a lot of oxygen, which then mixes deep into the ocean from the naturally occurring circulation patterns.

On the other hand, an unusually warm period stifles oxygen update and circulation, which can lead to “dead zones” where fish and marine life cannot survive.

“Oxygen varies naturally in the ocean quite substantially,” said Matthew Long, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) and lead author of new research into the impact of a warming climate impacts oxygen levels in the ocean.

“Without any human-driven climate change we could expect oxygen levels at a particular location to go up and down in such a way that low levels may be persistent for a number of years, followed by a period of high levels,” Long said in a recent press release.

Historically, teasing out this natural variability in ocean oxygen from warming-driven loss has been difficult, Long explains. “Loss of oxygen in the ocean is one of the serious side effects of a warming atmosphere, and a major threat to marine life,” he said.

“Since oxygen concentrations in the ocean naturally vary depending on variations in winds and temperature at the surface, it’s been challenging to attribute any deoxygenation to climate change. This new study tells us when we can expect the impact from climate change to overwhelm the natural variability.”

Research raises new concerns for ocean health

Distinguishing ocean deoxygenation caused by natural variability from climate change is the focus of Long’s research, published this week in Global Biogeochemical Cycles, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

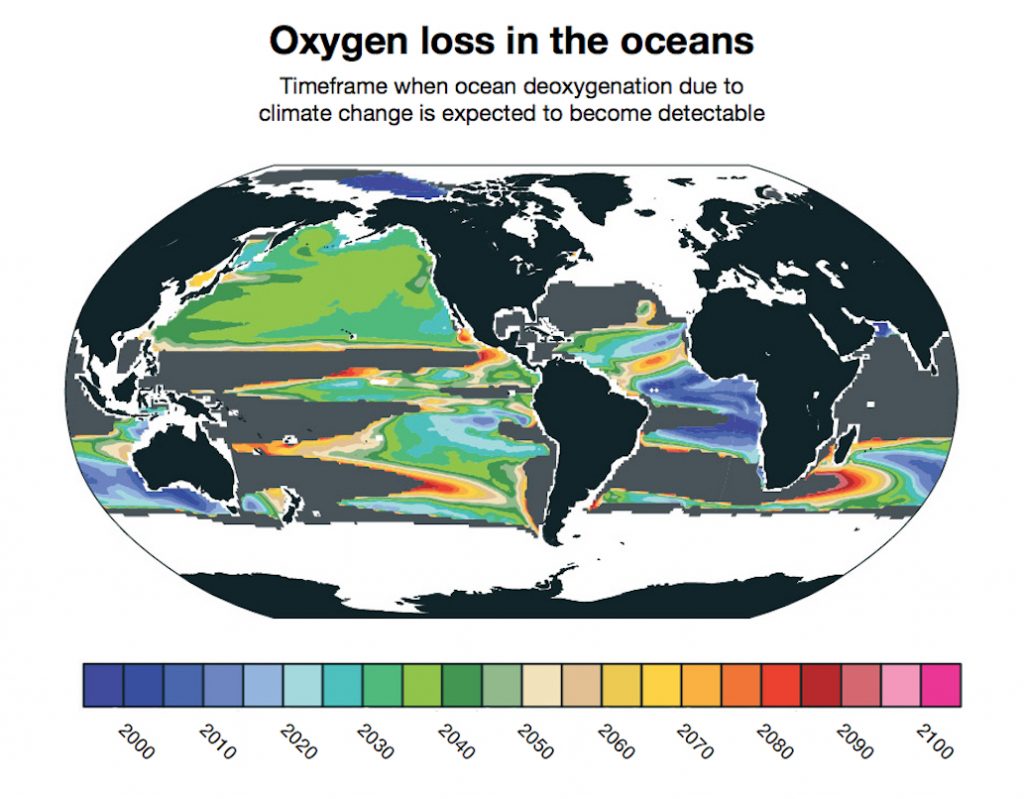

In a study titled “Finding forced trends in oceanic oxygen” Long and his colleagues found that ocean deoxygenation from climate change can already be detected in the southern Indian Ocean and parts of the eastern tropical Pacific and Atlantic basins. The research also determined that a more widespread loss of oxygen from climate change will likely be seen between 2030 and 2040.

Long’s team used the output from more than two dozen model runs of NCAR’s Community Earth System Model for the years 1920 to 2100 , with each subsequent run starting with tiny variations in air temperature. As each model run progressed, these small differences grew and expanded, affording a set of simulations useful for studying questions about change and variability.

Using these simulations to study dissolved oxygen, the simulations guided the researchers on past oxygen concentration variability. With this foundation they could then determine when ocean deoxygenation is likely to become more intense than at any point in the modeled past.

With this same dataset, the research team mapped ocean oxygen levels, visually representing where waters are oxygen rich at the same time that others are oxygen starved. From this mapping researchers could determine distinct patterns between natural variability and climate change in ocean oxygenation. What’s more, the maps will serve as a useful resource for deciding where to place oxygen monitoring equipment for ongoing research, crucial for sharpening the picture of ocean health and change.

“We need comprehensive and sustained observations of what’s going on in the ocean to compare with what we’re learning from our models and to understand the full impact of a changing climate,” Long said.

One more assault on ocean health

This new study adds yet one more offense to the health of the world’s oceans. Increased uptake of CO2 from the atmosphere causes ocean acidification, rapidly warming waters imperil coral reefs across the globe, highlighted by recent news that 93 percent of the Great Barrier Reef has been impacted by the most severe coral bleaching event on record.

Add to all this the persistent pollution and plastic waste in the oceans.

As oxygen levels become more pronounced, the resulting dead zones could have serious affects on marine ecosystems and sustainable fisheries.

The ocean itself is the living, breathing source of life on earth. We ignore its future health and vitality at our own peril.

Featured image credit: Narcah, courtesy flickr

Graph courtesy of AGU